Five years ago people were busy strapping Fitbits to their wrists and tracking their steps. Today they are doing it for their race horses.

This is just one piece of tech from a new breed of European startups trying to transform the business of animals — from farming to racing to husbandry.

Some of these startups are proposing seemingly bizarre solutions (e.g facial recognition for cows or robot chicken carers) but they are already out there disrupting big markets.

Farming in the European Union alone makes revenues of around €400bn a year.

Here are some of the most exciting companies out there today in European animal tech.

Chicken robots

Faromatics: Chickens as “business partners”

Rearing broiler chickens for meat is a brutal, low-margin business.

“Farmers make on average 15-50 euro cents per broiler and so it is hard to make a reasonable living with less than 100,000 birds,” says Heiner Lehr, chief executive of Faromatics, a company making robots that help chicken farmers monitor their flocks. And while consumers increasingly want the chickens they eat to be reared in humane conditions, the reality is that poultry farmers have very limited time to squeeze in all the checks they need to do on the birds.

Faromatics’ ChickenBoy is proposing to help. The robot, armed with a series of sensors, is suspended from the roof of the chicken barn and zooms around measuring things like air quality, humidity and temperature. It can now even measure levels of ammonia, an indicator for whether the litter in the barn is too wet or not. It can detect dead birds, and can analyse if there is any unusual rise in mortality rates.

It will also analyse the chicken feces and can detect intestinal disease, up to 48 hours earlier than a farmer would, says Lehr. “It is not that it is much cleverer than a farmer, but the robot works 16 hours a day and is much more consistent in recording everything, so it can pick up on signs that a farmer might miss.”

Lehr, who has a unique combination of expertise in quantum physics and chicken feces (“it’s not a great pick-up line,” he says), says this kind of smart livestock farming is only now starting to become possible, as the cost of components such as sensors has fallen and machine learning software has become more accessible. It is only once such robots get below the €1000 sale price that they become a viable proposition for farmers.

“We needed to get the return on investment down to a year. A longer payback time isn’t possible for a new technology that isn’t yet fully established or understood,” says Lehr.

Catalonia-based Faromatics is beta testing the ChickenBoy at the moment with farms in Spain, Holland and Germany, also looking at expanding to the UK and France.

The 12-employee company has so far raised €2m and is hoping to reach profit in 2020 following a full commercial launch. Eventually the same robot could be adapted for monitoring other kinds of poultry, or even pigs or cows.

For now, Lehr is hoping to bring a small revolution to chicken farming - a little bit like the Japanese management techniques emphasising lifelong employee wellbeing, which became popular in the 1980s.

“We’d like to change the way farmers consider their chickens, from just units of production to business partners,” he says. “Short-lived business partners.”

Other tech companies in this market include:

A French company, founded in 2016, that makes a robot called the Spoutnic, that moved the chickens around the barn or yard to help them get more exercise and avoid developing leg problems. It also helps avoid the problem of “floor eggs” when chickens lay their eggs in non-designated areas, making them hard to find and collect.

The French robot company has developed the Octopus Poultry Safe robot that aerates and disinfects the litter in a chicken barn. It listed on the Paris stock exchange in 2018, valued at €26.5m and raising €2.2m

Fitbits for horses

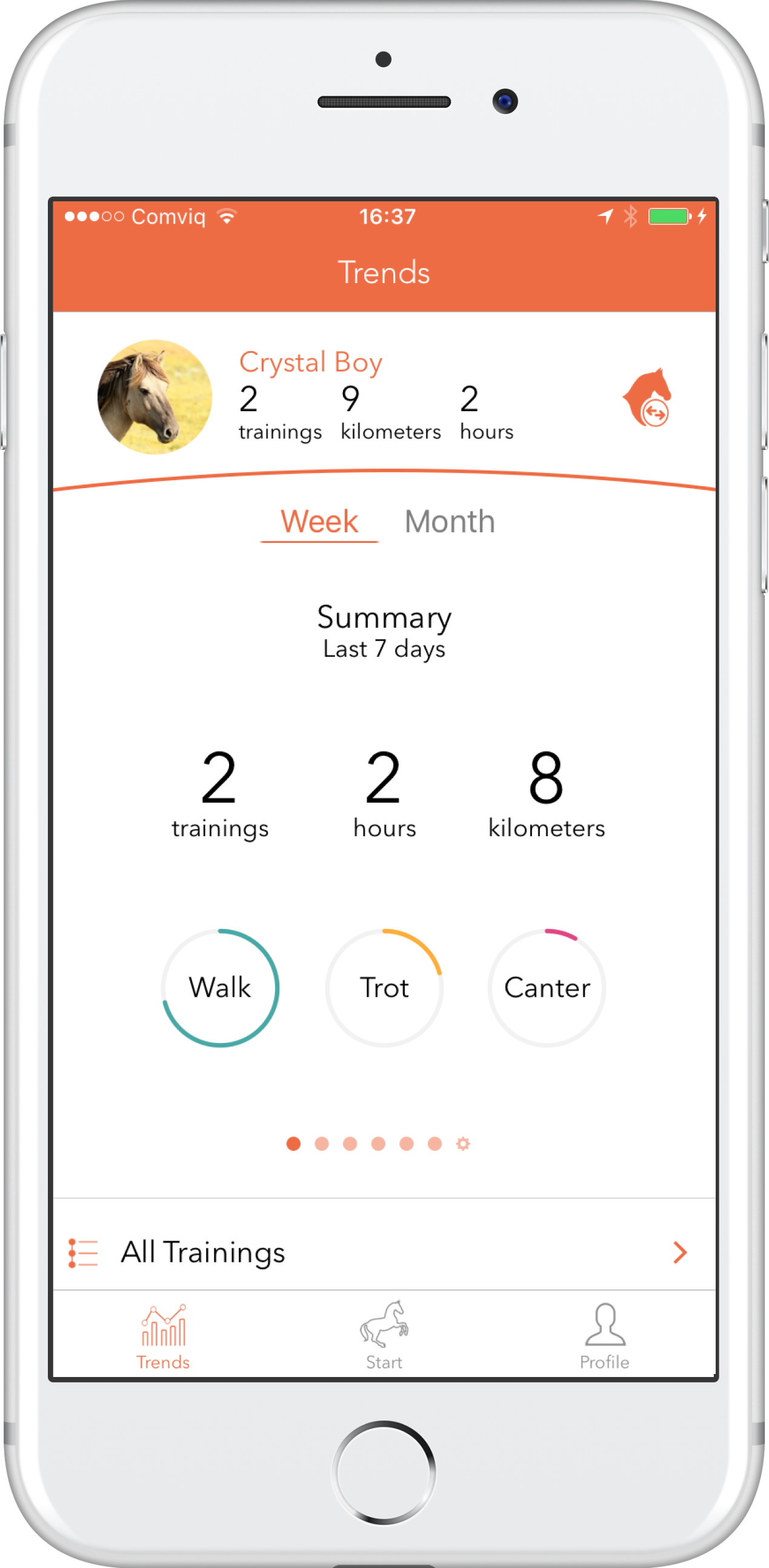

Equilab: Strava for horses

When an injury forced Per Ericsson to give up competing in triathlons, he turned to riding. But the Swedish signal processing expert soon became frustrated that none of the tracking technologies he had used to measure his athletic training seemed to exist for horses. So he decided to make his own.

The Equilab app taps into sensors in a smartphone and uses them to analyse a horse’s gait, speed and other movements. It can suggest ways to optimise training, and can pick up if a horse has suffered an injury.

While motion sensors are everywhere these days, the Gothenburg-based company’s challenge was training an algorithm to interpret a horse’s gait accurately, says Adam Torkelsson, CEO and Ericsson’s co-founder of Equilab. The equestrian market also has very specific needs. One common exercise, for example, is getting horses to go around in circles, which tests their balance and suppleness. Most horses have a “better” and “worse” side for making circles, and this is one of the aspects that Equilab’s software can now pick up on, Torkelsson says.

World Cup medallist and horse trainer Magnús Skúlason and Swedish endurance medallist Charlotte Tillman are among the celebrity users of the app, but the big opportunity is in the mass market of 90m riders worldwide.

So far Equilab, which was founded in 2016, has persuaded around 360,000 riders to use the app in the UK, US, Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, and Brazil. The company has a freemium business model, where basic access to the app is free, but users pay around £9.99 a month if they want access to premium features, such as a safety-tracking function that allows riders to share their route with friends and family, and which will call for help if they suffer a fall.

The company raised SEK3.5m in a seed round last year, taking its total raised capital to SEK7m, and is starting talks with venture capitalists about further funding. Torkelsson says he would like to at least double the size of Equilab’s 9-person team over the next year.

Equisense: Fitbit for horses

Keen riders Benoit Blancher and Camille Saute created a wearable tracker for horses to help them track their own training sessions. Fastened on the horses girth, the €199 devices measures the horse’s motion, and a new version, which will become available in the summer can also measure heartbeat.

“We had to figure out how to do that because when you monitor heartbeat on humans there is less hair,” says Blancher. “But the technical challenges are now solved.”

The French company, founded in 2016, has so far sold more than 6,000 sensors, mostly to buyers in France and Germany.

The 15-person company has raised around €3.5m in funding, including a seed round and a crowdfunding campaign. Blancher says it is on track to reach profitability this year.

Other companies in this market include:

A UK-based startup that has created a wearable device that alerts owners to horses’ health problems. It can also track exercise session — and even a horse’s sleep. Raised a £160,000 angel round in 2018.

This Irish startup makes a lighting system, including stable lights and a light mask worn over a horse’s face, which helps regulate fertility. Mares’ breeding patterns are heavily influenced by light and breeders are using the light therapy to encourage the reproductive system to activate earlier in the year.

Connected Cows

Cainthus: Facial ID for cows

It is cute that Cainthus can identify each individual cow in the herd by its facial features and the pattern of its pelt, but that’s not really the main point. The Irish startup is trying to solve the biggest problem in agriculture overall: a lack of data.

“If you can’t measure something accurately you don’t know if it is working. You don’t know if the increased yield of a field is down to the fertiliser you used or if an increase in milk production is really down to the feed,” says Cainthus founder David Hunt.

Hunt, a graduate of California’s Singularity University and now a lecturer there, wants to bring more measurability to farming, with cheaper sensors and computing equipment making it possible to track individual animal’s much more closely than before. It makes sense to start with computer vision because it is one of the cost effective ways to monitor a large number of animals, and with dairy farming because margins in this business are a little higher than for other areas of livestock.

Dairy farmers have one of the highest rates of tech adoption.

Dairy farmers have one of the highest rates of tech adoption. Farmers make around $600 in milk production from each cow per year and are willing, by Hunt’s reckoning, to spend some $25 to $100 of that on tech to improve the business.

Cainthus installs an array of cameras — often around 20 — in a barn, that will monitor the cows and alert farmers to any health or feeding problems. Hunt says this results in savings on labour costs and also on feed, as tighter monitoring can lead to farmers wasting less. An added benefit — though harder to quantify — is that cows tend to be less stressed when there are fewer human visits to their barn.

The company has installed the equipment on farms in 9 countries and is just about to start a big rollout in the US and Canada. It raised an undisclosed sum from food company Cargill last year.

Eventually the plan is to roll out the monitoring technology to other animals. Work on pigs has already started.

Other companies in this market include:

This Dutch startup has created an artificial intelligence-based service that collects data from cows and use that to detect conditions like mastitis and lameness quickly. It can also tell farmers which cows are in heat and the best time for insemination, as well as picking up on digestive disorders. The company has raised €6.7m to date, including a €4.2m series-A round last year led by Russian VC Sistema.

An Irish company makes wearable sensors that alert farmers to cows that are calving and when they are in heat. A sensor placed on the tail of the cow can tell when a cow is in labour and can alert farmers if the process goes on for too long. The company raised €15,000 in 2017.

The Edinburgh-based company has created a wirelessly connected bolus that is inserted into a cow’s rumen to monitor acidity levels. This helps identify digestive problems early.