Last year, Antoine’s girlfriend gave him an ultimatum: it’s me, or the startup.

He chose the startup.

Which is how Antoine*, a 20-something French founder who’s been running his company for several years, came to live in the newly opened co-living space run by Parisian startup campus Station F.

It’s kind of nice, he says, to be able to really focus on the business.

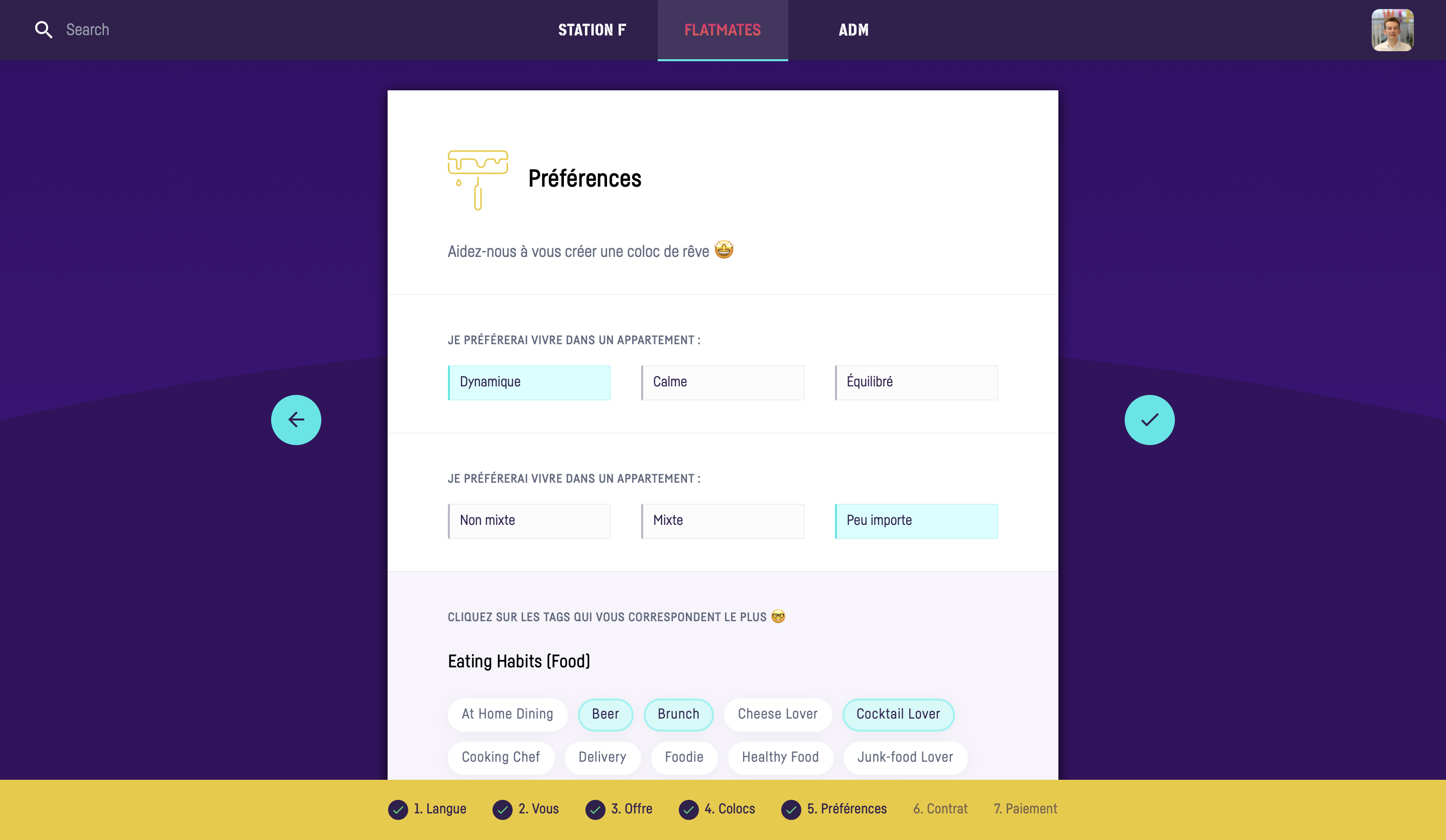

Antoine now has four flatmates. They’re all founders. They share an apartment on the seventh floor of the “Atlantis” block, a 30-minute walk (or a 10-minute scooter ride) away from the Station F Campus where they all work. And they’ve been grouped together by Whoomies, a matchmaking app for flatmates, based in (of course) Station F.

This is not luxury living. The co-living apartments are “outside of Paris” (it’s in Ivry-sur-Seine, a neighbourhood just south of the ring road that surrounds the most central part of the city). It’s near a rubbish facility, several busy roads and a mass of train tracks.

The apartments are basic, but pleasant. The bedrooms are small, but cheap (€399, or €549 for a private bathroom, per month). And the sunrise from the bedrooms on the 11th floor is rather lovely.

But for many residents, location and decor aren’t important. “Flatmates” (as the co-living space is called) is a useful landing pad in Paris. It’s notoriously hard for non-French people to find flats in Paris — and it’s expensive for everyone.

It’s also helping some startups at Station F attract staff; they can offer them a cheap bed in the co-living space while they figure out whether Paris (or the company) is for them. The minimum stay is one month, and they can stick around for as long as their company is in a Station F programme (plus a three month period afterwards to find a new home).

Flatmates isn’t full at the moment, as construction work is ongoing; it has 350 residents, who have slowly been moving in since June last year, but eventually it will have 600. There will be a big lounge, a laundry facility (that doubles up as a library), a cafe-grocery shop, a gym, regular yoga sessions and on-demand poke deliveries. What more could budding entrepreneurs want?

City living

Co-living has become firmly associated with startup-world yoga babble, but it has the potential to be a huge, not just a niche, market. Investment into the sector is booming — growing more than 210% globally year-on-year since 2015 — as property developers, private equity firms, pension funds and venture capital investors start paying attention.

Numerous models are also springing up, targeting not just tech types but also university and business school students, and retirees.

Co-living’s biggest fans say this isn’t a fad: it’s the future of city living.

Colonies, a more upmarket version of co-living than Flatmates, which opened its first property in 2018, currently runs four apartments in Paris and two in Berlin. On offer are “beautiful private studios”, “amazing shared spaces” and “top-notch services” — and investors are interested.

Last week Colonies raised €30m from Idinvest and Global Founders Capital, to increase the number of properties it can offer its target audience: young professionals and business school students. Its rooms, slightly more spacious than those at Flatmates, start at €850 and head upwards of €1,200 per month.

On average, residents (who currently range in age from 18 to 62) stay for a year, says Colonies cofounder Alexandre Martin.

For the extra price, they get to retreat from adult life: Colonies takes care of cleaning and keeps the apartments stocked up with dishwasher tablets and loo roll. They also don’t have to cough up a huge deposit, and get a dedicated "experience manager" to look after them.

Hassle-free

Homefully, a Berlin-based co-living startup, is also proud to be “hassle-free”.

Its customers, says cofounder Sebastian Würz, are mostly young professionals who’ve moved to a new city, either in their own country or from elsewhere in Europe. They’re attracted to the convenience and social networks offered by co-living: homefully’s team helps them register in their new city and introduces them to new people.

On average, homefully’s customers stick around for eight to nine months — although Würz would like to see that increase to around 12 months. “The community is even better the longer people stay there; we want to avoid fluctuation,” he says. “But we want to provide flexibility; we don’t want to lock people into lengthy contracts.”

Homefully, which has raised €5.5m since launching in 2016, is now raising a Series A. “We want to be the co-living champion of Europe,” says Würz.

Coliving is easy to enter, difficult to scale.

The company currently has 1,000 rooms in apartments across eight cities, including Frankfurt, Berlin, Munich and Zurich. Occupancy rate is 95-100%, says Würz. With more cash in the bank, homefully plans to scale in its existing markets and expand into several new ones. Italy, Spain, Portugal, France and the Benelux region are all enticing, says Würz.

“Competition is on the rise — especially local competitors,” he says. “But no-one has managed to scale over multiple locations and countries yet.”

“Co-living is easy to enter, difficult to scale.”

Yoga babble

Co-living could become the preferred residential model for an enormous number of people in Europe. “The majority of co-living companies are targeting one fundamental need: easy access to real estate for new city dwellers,” Gui Perdrix, a co-living expert, says. “It’s not at all startup sexy.”

JLL, the real estate services company, estimates that there are around 9,000 co-living beds already available in Europe, with 30,000 either being built or in the development pipeline. 16,000 of those are in the UK. That’s “enormous growth in a short period of time”, says Richard Lustigman, head of co-living at JLL, who’s been tracking the sector for three years.

What’s more, 79% of co-living buildings in the pipeline have 200 bedrooms or more — which means they’re big enough for institutional investors to back. Private equity firms through to pension funds are looking closely at (and investing in) co-living property developments, while mid-size to large residential developers are building them.

Meanwhile, on the operational side of things, family offices and venture capital investors are starting to back co-living operators.

“Co-living is going to be a major sector moving forward,” says Lustigman.

Venture backable?

Not everyone is convinced that it makes sense for VCs to back co-living companies, however. “Whether the returns are there for the [operational] side of the market remains to be seen,” says Lustigman.

Co-living companies are testing out different financing models. The Collective, a UK-based co-living company founded in 2010, which has raised over $1bn, invests in, develops and operates co-living spaces.

Whether the returns are there for the [operational] side of the market remains to be seen.

Colonies, meanwhile, has a commitment from real estate LBO France to spend €150m developing co-living spaces, which Colonies will then operate. As a result, money invested into the startup by VCs finances operational and tech costs — not the real estate itself.

“VCs shouldn’t finance real estate,” says Christopher Priebe, a partner at Colonies investor Global Founders Capital (GFC), adding that it will be co-living companies who can nail their operations and customer experience that will stand the test of time.

Lustigman reckons co-living companies need to be somewhat invested in both the property and the operational side of the business. “As an asset-light operator, there is longer-term more risk to you — you have no vested interest in the asset,” he says — despite having to front the costs to kit out a building.

Würz has a different point of view. Homefully has an asset-light model, leasing properties ranging from individual apartments through to whole apartment buildings, on a long-term basis. “[Co-living] might not have the same growth numbers as a SaaS [software-as-a-service] company, but it has strong margins, low risk and a good profitability outlook compared to other models.”

“The limiting factor is capital — it’s a capital intensive business,” he adds.

“A lot [of co-living companies] are playing with high growth, but those financials only make sense with a certain amount of spaces,” says Perdrix.

Tech Farm, a Swedish co-living company, wants to launch 100 co-living properties across the world. The Collective, which currently has two locations in London and one in New York, and operates 9,000 rooms, aims to have 100,000 rooms across the world in the next five to 10 years. Colonies plans to open 100 new locations by the end of 2021, focusing on France, Germany and the Benelux region.

At some point there will be consolidations — I don’t think many of the small players will make it.

“At some point there will be consolidations — co-living is not winner-takes-all. There’s room for two to three market-leading co-living companies in Europe, each with a slightly different proposition,” says Würz, who plans to buy some small, local co-living companies as part of homefully’s expansion strategy. “I don’t think many of the small players will make it.”

“We expect to see big consolidation in the operating side of the sector,” says Lustigman. “There are too many small operators, which don’t have a big enough portfolio to drive the revenues you need to build a sustainable business.”

The Collective has even raised a £650m to invest in co-living companies — and acquire others.

The future of co-living

Students and startup founders might have been the earliest adopters of co-living, but are not the sector’s only target customer.

“Co-living will diversify — even though the branding is around millennials, you have people who are 45 or 50 staying in those spaces,” says Perdrix. “50-70 year olds who just want to live together, but not live in an elderly home, who are older but still active — there’s a huge market there, untapped.”

People who are older but still active — there’s a huge market there, untapped.

Lustigman agrees: “There’s a strong play on the downsizer and the retirement sector as well.”

For the trend to truly take off, the real estate sector — and cities — need to step up.

“It’s critically important that regulation is there to protect customers and ensure that quality standards are maintained — but it’s also important that authorities don’t over-regulate, and allow innovation to flourish,” says Lustigman.

Supporting the nascent co-living sector could also boost the tech sector as a whole, he adds — as Station F is hoping to demonstrate with the Flatmates development.

“In the future, cities won’t necessarily compare themselves against other cities in [their country], but with other global cities. And if those are cities able to attract talent, attract innovative employers, bring forward new tech businesses — and understand that co-living goes hand-in-hand with that as a living solution — then certain cities will not be able to compete.”

* Not his real name.