Some say hydrogen is the only real alternative to fossil fuels when it comes to air travel.

The team behind Swedish startup Heart Aerospace don’t agree. They think they can build an all-electric aircraft for domestic flights — and they’re getting closer.

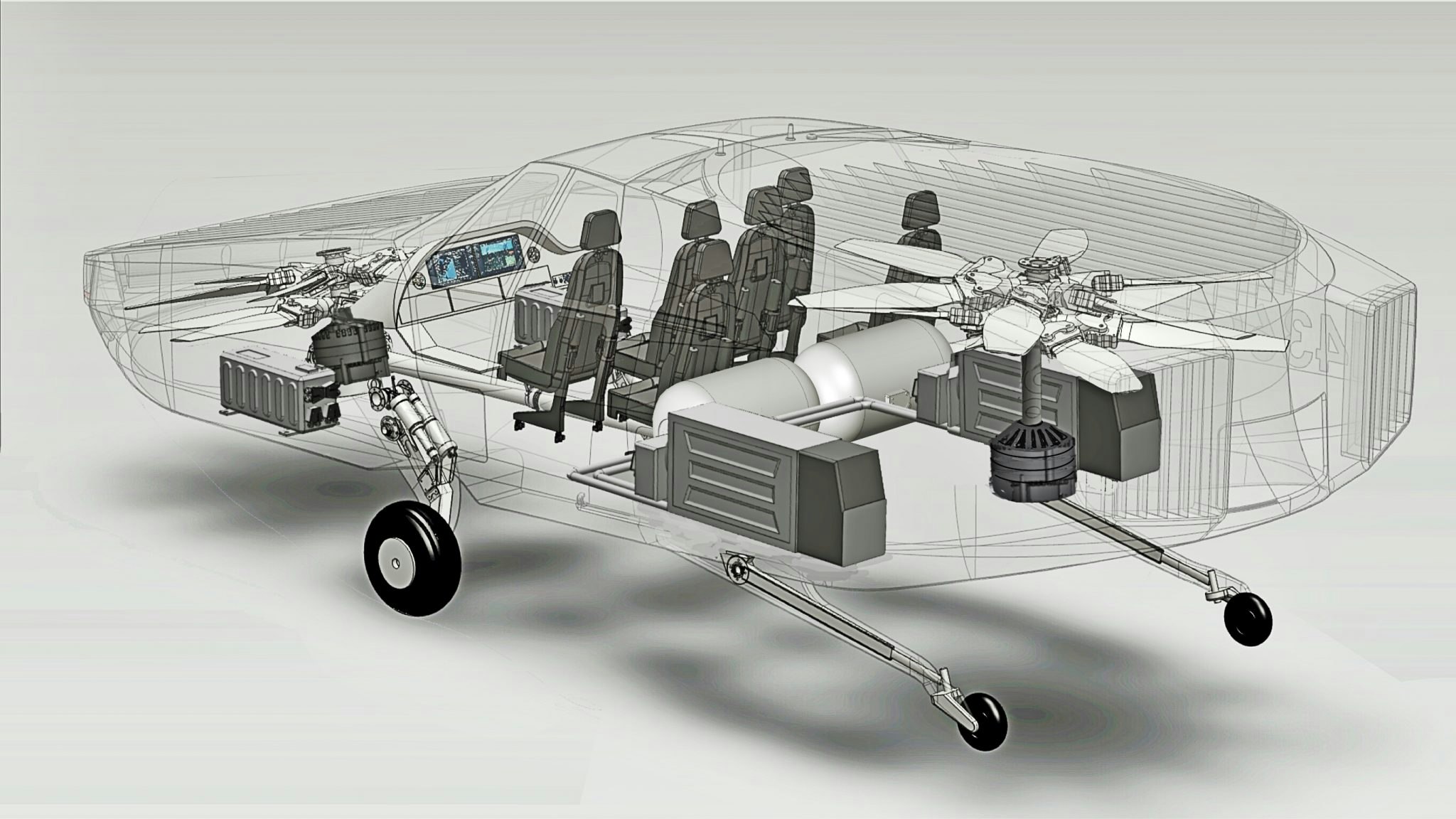

Today, Heart Aerospace is unveiling its electric drivetrain and battery technology, targeting short-haul flights, for the first time. The plan is to build 19-seater planes that could provide all short-haul air travel under 200km — and if everything goes to plan, the company will be certified for commercial operations by 2025, completely free from fossil fuels.

A green giant

Investors don’t think it sounds like such a wacky idea. Last week, Heart Aerospace won a €2.5m grant from the European Innovation Council (the maximum amount that could be awarded) as part of the first tranche of its “Green Deal” funding.

It also raised €2m from VC firm EQT Ventures and impact investor Norrsken in 2019, and has received financial support from the Swedish government agency for research and development, Vinnova.

Heart Aerospace’s founder, Anders Forslund, who started the company at Elise, a Vinnova project about electric aviation, in 2018, thinks the business will only take off with continued support from both the public and private sector.

“In order to make this happen. It has to be some sort of public-private partnership,” Forslund tells Sifted.

Apart from the support from the EU, Forslund is referring to the fact that Heart Aerospace has had a lot of support throughout the Nordics. Sweden has committed to make all domestic flights fossil-fuel-free by 2030 while Norway has pledged to make all domestic flights 100% electric by 2040.

On top of that, despite the fact that Heart Aer ospace can’t actually prove that its technology works yet, eight airlines have expressed an interest to purchase 147 aircrafts worth approximately €1.1bn.

“The interesting thing about the airlines in the Nordics and especially in Norway, is that they need this,” says Forslund. “It's not something they can opt-out of, so they want to be proactive about it, and I think that's one of the reasons they're so supportive.”

Hydrogen vs. electricity

Amongst fossil-free transport fans, there’s a fierce debate raging: hydrogen — or electric? So far, hydrogen is by far the most popular. On Tuesday, the world's largest airliner manufacturer Airbus, announced that the company plans to build two hydrogen-powered aircraft to carry between 120 and 200 people.

Even aircraft startups with a similar plane size to Heart Aerospace’s are favouring hydrogen instead of all-electric because Lithium-ion batteries only have an energy density of 300 watt-hours per kilo. And while electrical propulsion systems can compensate for this by being more efficient, there is still a lot to make up. This means that electric aircraft, like some flying taxis, have a relatively short flying range.

But according to Forslund, his prototype has what it takes.

“It is really like a jet engine or a turboprop jet engine, in power that is, but it's all-electric,” he says.

“We are not building a flying car – we are building a very conventional plane. It will be safe, efficient and reliable, and the only sort of innovative part of our plane is the electric propulsion system and we are working on making that as efficient as possible.”

Competition is hotting up, though. The British startup ZeroAvia, run on hydrogen, has already completed the first-ever flight of a commercial-scale electric and hydrogen-powered aircraft in the UK and plans to be flying 20-seater planes within three years.

But Heart Aerospace is sure it has a shot at the market, in part because of the fact that electricity is much cheaper than hydrogen.

“What we see is that for short routes under 400km, and with the battery technology we have today, electric is by far the most cost-efficient. It's the best use of energy because if you want to generate hydrogen you lose a lot of energy in that process,” Forslund says.

“In this space, you really have to make the unit economics work.”