As the war continues in Ukraine, countless people from the country’s tech community are facing huge challenges. Some are now serving in the military, others have been relocated to new, unfamiliar countries and are rapidly searching for jobs, while others are trying to keep working from close to the front line.

Sifted spoke to three tech workers and asked them to recount their experiences of the invasion. These are their stories.

Oksana Vorobiova, 28

Unreal Engine developer for Pingle Studio, a games development service platform, Dnipro (central Ukraine)

As far as I know, our district is still relatively safe. There are no troops here. Some villages on the border were bombed recently. But for now, the city itself is safe.

Today I went to the hospital to do a blood donation, then I slept for half of the day. Then I worked a little bit. Today is one of the laziest days since the war began. For the past few weeks I’ve been spending a lot of my time helping people get hold of bulletproof vests.

My friend is currently serving in the military forces, and when I discovered that they do not have basic protection I decided to start helping. I’m not an armour-maker or a seamstress, so I wasn’t sure if I’d be able to help, but so far I’ve been helping coordinate supply of materials, and I’ve gotten them about 60 vests. Now we have an order for about 100 helmets, vests and night vision devices, and the total bill is about $80k, so now we're more focused on collecting money.

Normally I write C++ code in Unreal Engine, and I’m trying to keep doing some work as much as I can. It is critically important for the IT sector in Ukraine to continue day-to-day work, because we are working mostly for foreign companies. That means cash flow in Ukraine and that means paying for goods and services to sustain income.

I don’t really remember the past month or how it’s passed day by day. But I can tell you how my emotions have changed. First of all it was a rush of disbelief. Then it was fear, but as we have not seen real combat here yet, there is nowhere to put that fear. It is easier to deal with fear, because with time it turns to anger. I'm not really experienced in how to deal with anger, because anger should have an outlet and it's not easy to find it.

To donate to Oksana’s vest-making fund, use Paypal 26009045106101 – Voloshyna Ludmyla Viktorivna

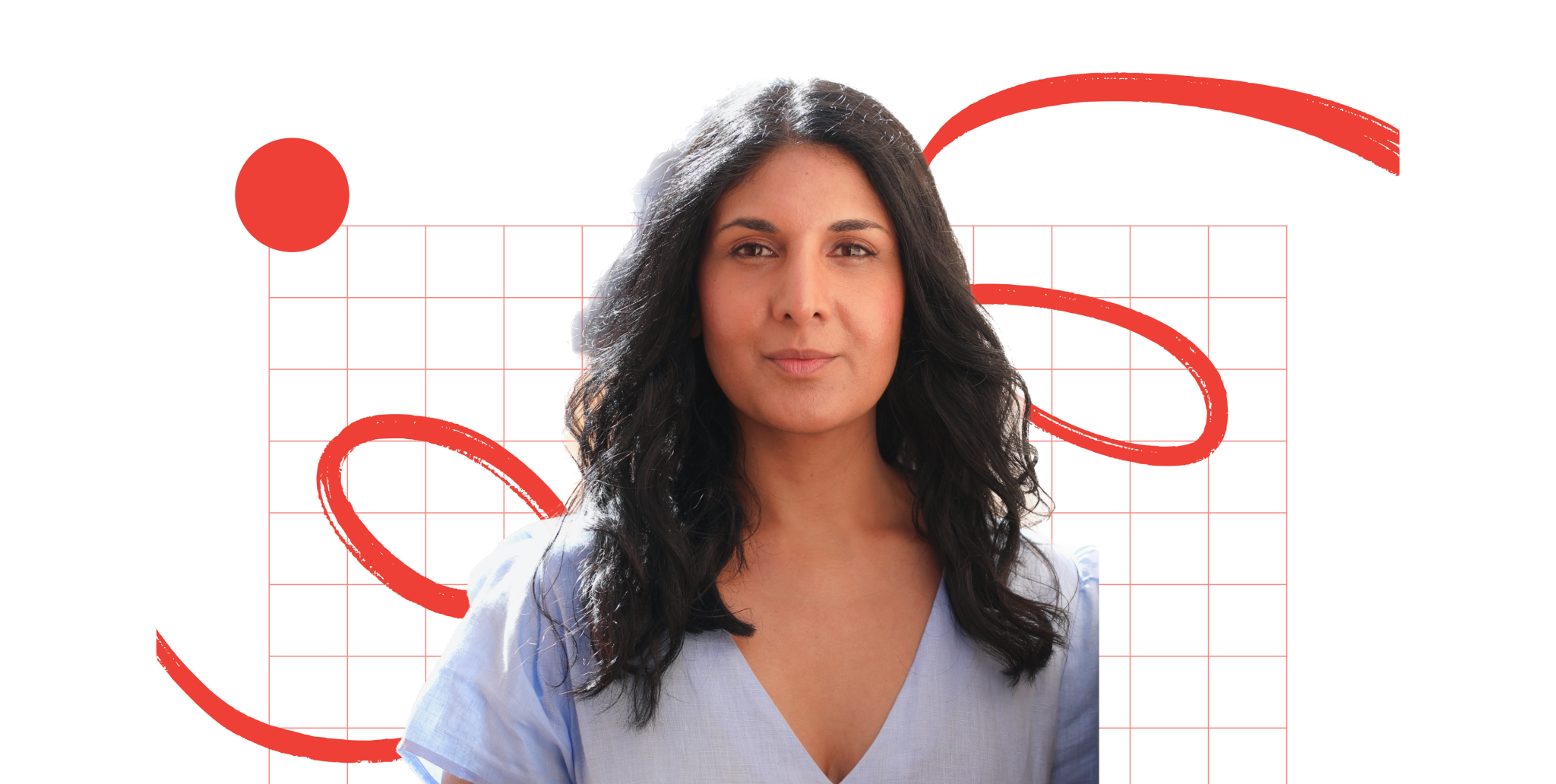

Nastya*, 20

Employee at a global IT company, now in Budapest

On the first day of the war, I was super disorientated. I woke up, everything was blurred. But I have a tradition: no matter where I am, no matter what’s going on, I will always go and grab some coffee. So that’s what I did. There were tanks rolling down the streets as I walked, but some businesses were still open.

I was lucky to have escaped Kyiv within the first few days of the war. My mum and my dog are with me now (they joined after the situation got much worse) but my brother had to stay in Kyiv. The current law states that men have to stay in Ukraine, so he’s looking after my grandparents who are too old to travel.

👉 Read: The man who convinced Musk to give Ukraine free Starlink

At 7am on February 25, I shoved a few things into an Adidas bag and got into a car with the son of my mum’s friend, who I have known for many years. He offered me a lift alongside two other guys and a woman I’d never met before. We drove in the direction of western Ukraine, to the Moldovan border. As we tried to cross, the three guys were told to go back to Kyiv as Ukraine needs men on the ground to fight. The guys took the car; myself and the other girl got out and crossed the border on foot. It was nighttime. We were the only ones walking, while everyone else, who were escaping like us, queued up in cars.

We eventually got to Chișinău, the capital of Moldova, via a friend of my mum’s friend who drove us there from the border. From Romania, we caught a flight to Austria, and from Austria to Paris (both flights were six times more expensive than usual).

I came to Paris quite deliberately: it’s always been my dream to live there. I’ve wanted to work in art and fashion my whole life, but these industries are not well-developed in Ukraine and the salaries are super low — which is why I currently work for an IT company.

My friends in Kyiv are still getting coffee from our favourite cafes, and have even taken yoga mats to the bomb shelters to do some sport

But I was only in my dream city for just under three weeks before my company ordered me to go to Budapest, like my other Ukrainian colleagues. I’m guessing they want us here because the city is so cheap. I explained I would prefer to live in Paris, where I could scout around for some more freelance work on the side (having a Ukrainian salary in Europe is difficult due to the poor exchange rate) but they threatened to fire me if I didn’t comply.

Let me just add here that I’m not a victim; I’m privileged to have escaped. But I hate Budapest. People are cold and distant, and Hungarians have always been super negative towards Ukrainians. At the moment, I’m continuing to look for jobs in fashion: I’m having six or more calls a day, knocking on every door. I think people are really looking out for Ukrainians at the moment. Before the war, I got no replies when I reached out to people in the fashion industry. Now, I’m getting a lot more responses.

Things are better than they were, you know. People can get used to anything. Now, I’m calling friends in Kyiv who are still getting coffee from our favourite cafes, and have even taken yoga mats to the bomb shelters to do some sport. I’m trying to stay positive. I’m in a position of safety.

Ivan*

DevOps engineer at GlobalLogic, a digital product engineering service provider. Serving in the National Guard of Ukraine

Generally everything is fine. As I wake up at 6am and go to bed at 10pm, my sleep-wake cycle has partly shifted. There’s someone guarding our post 24/7. My family does not know that I volunteered for the army yet; only my girlfriend, my sister and one friend know about it. I didn’t tell my family because if they found out I would get countless unnecessary arguments that could be an obstacle that would hold me back from concentrating on my goals in the army.

The training was mainly on providing the first medical aid, a so-called two-hour crash course at which we were shown how to use medical tourniquet belts and first aid kits — what to use and when. We had tactical training in shooting from different positions, a lot of theory on combat and transporting wounded comrades and shooting from weapons assigned to you (AK-74). We were allowed to shoot only 20 rounds at different targets at different distances.

It was a little awkward to move from a comfortable chair to rather 'Spartan' conditions

It was a little awkward to move from a comfortable chair to rather “Spartan” conditions, but I've tried different jobs in life and some of my new colleagues were surprised because I'm not the stereotypical tech geek they used to see on the street or hear in stories. In general, it is a strange feeling, but there is an understanding that you must contribute to this fight against those who can harm your loved ones.

I’m planning to stay here as long as martial law is in place. When it’s over, I’m planning to go back to work at my company and will continue to support the armed forces as a volunteer.

Tim Smith is Sifted’s Iberia correspondent; he tweets from @timmpsmith. Miriam Partington is Sifted’s Germany correspondent and future of work reporter; she tweets from @mparts_