A growing number of vertical farming startups — businesses using a style of high-tech farming where crops are grown on stacked trays indoors — have popped up in Europe over the past decade.

Their mission? To create a more sustainable and less seasonally-dependent food chain — and, possibly, make heaps of money doing so. Over 6bn people are projected to be living in urban areas by 2050, and vertical farming could offer a more land — and water — efficient way to feed them than traditional farming. The market is projected to grow substantially in the next few years, and reach $12.77bn by 2026, up from $2.23bn in 2018.

Leading the pack — at least in terms of funding — is Infarm, a Berlin-based startup founded in 2013 which has raised more than $300m since launch from big investors like Atomico. But it’s not the only vertical farming startup catching the eye of VCs: France-based Jungle raised €42m in March 2021, while UK-based Jones Food Company raised $10.9m in June 2019.

We’ve spoken to most of the European major players — and the VCs backing them — to find out where the market is at now, where it’s heading and what challenges lie ahead.

Who's in the running?

The latest addition to the vertical farming pack is UK-based Syan Farms, which launched last month and has built its first vertical farm in Northamptonshire.

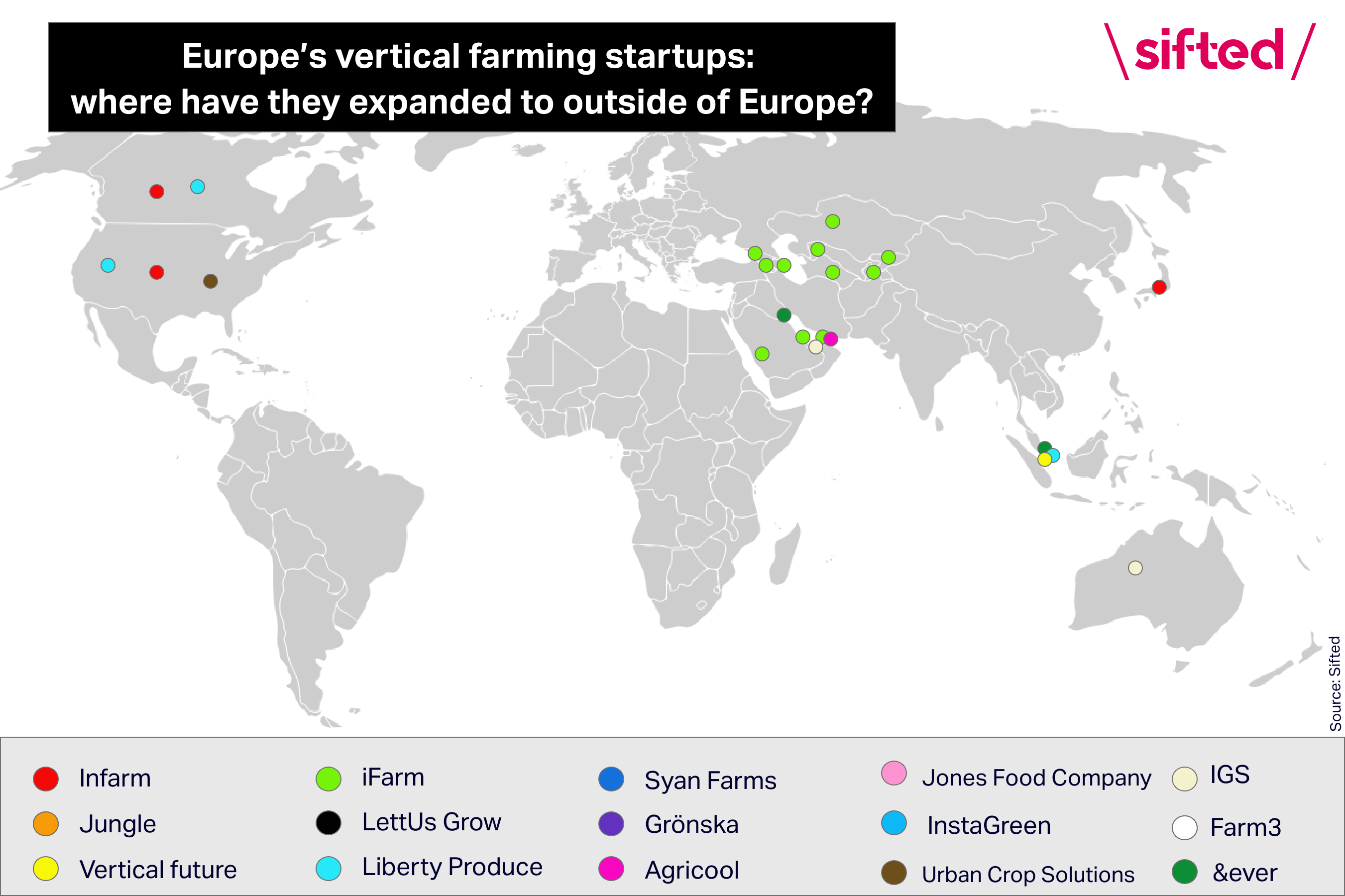

Other relative newcomers include vertical farming startup Liberty Produce in London, which doesn’t sell crops commercially but runs vertical farming research trials to find out how to optimise plant health. It’s already expanded into the US, Canada and Singapore, and is looking into expanding further into southeast Asia and Europe.

Generally, all the companies grow the same stuff: leafy greens, herbs and microgreens for commercial sale or research purposes. Some offer more unique crops; Belgium-based Urban Crop Solutions is growing medicinal plants, Jungle is growing flowers for the perfume industry and Finland’s iFarm has managed to grow more substantial vegetables like cucumbers and peppers. Infarm tells Sifted that it will grow chillies, mushrooms and tomatoes in the future.

Many offer their technology through partnerships with big supermarket chains like Marks & Spencer in the UK, Monoprix in France and Edeka in Germany for shoppers to buy produce. Emmanuel Evita, global communications director at Infarm, calls this “farming-as-a-service”. Retailers purchase the produce, while Infarm builds the farm in-store and maintains the installation, plants the crops and monitors their growth.

Consumers pay roughly between €1 and €3 for vertically farmed products in the supermarket. The growing units themselves cost anything from £100 to £5m depending on the customer’s needs.

Partnerships with restaurants haven’t taken off as much — although Belgium’s Urban Growth Solutions recently entered a deal with IKEA Malmö’s restaurant division to grow vertically farmed crops in an on-site container.

Which markets are they trying to win?

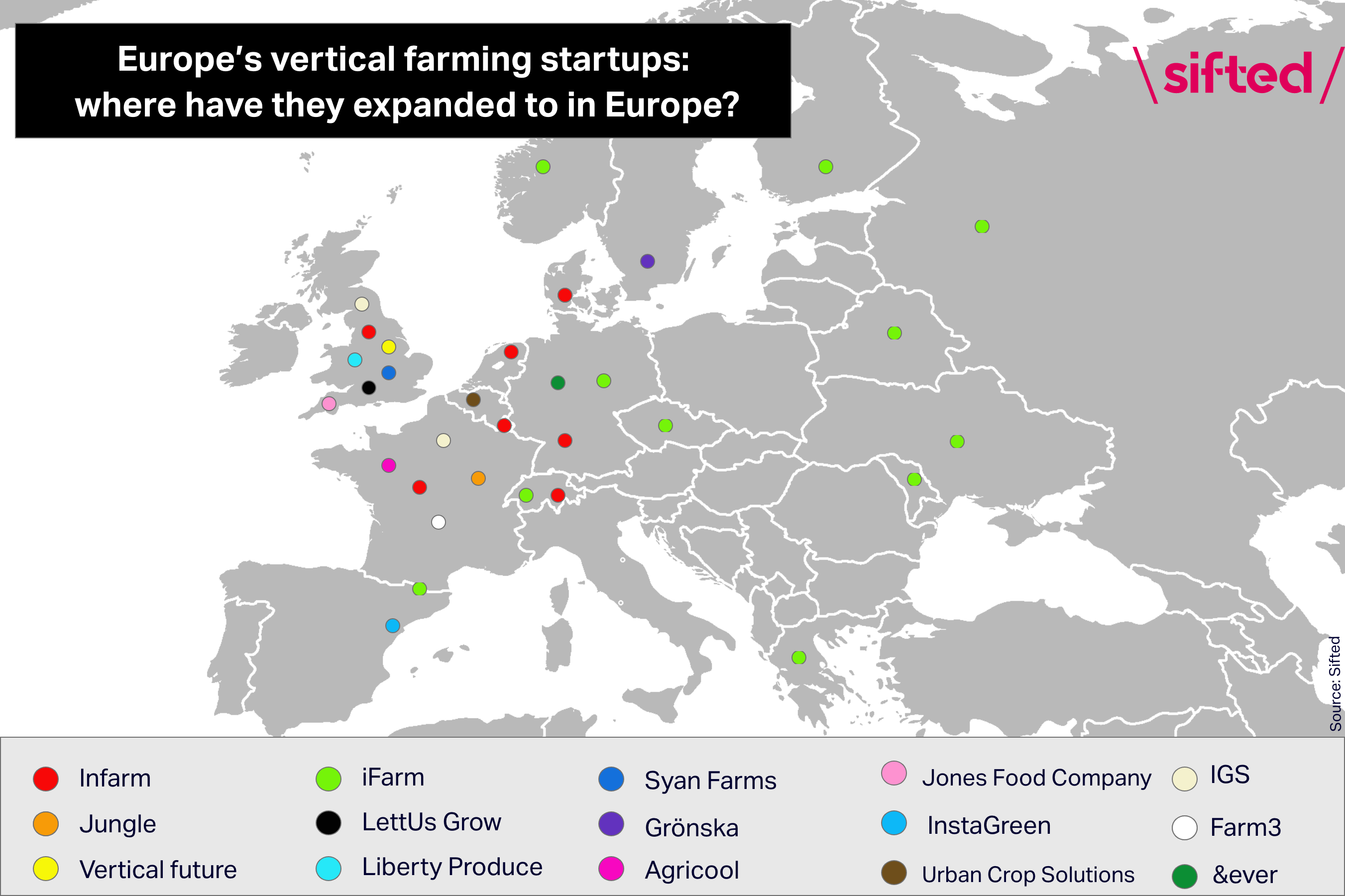

Northern Europe has had a lot of attention. Germany's Infarm has now expanded to six other European countries — Denmark, France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, the UK and Switzerland. Finland’s iFarm has also expanded into six European markets — Germany, Switzerland, Andorra, Norway, Greece and the Czech Republic.

Max Chizhov, cofounder and CEO at iFarm, which has developed a vertical farming SaaS solution, says that northern European markets are popular “because the climate doesn’t allow people to grow fresh produce all year round there.”

“The hot and water scarce climates of the Middle East and North Africa” make them a good target as well, adds Chizhov.

Parts of Asia are also attractive, especially Singapore. “Food sustainability is a global issue but in places like Singapore, there is a high dependency on food imports, making it a better candidate for vertical farms,” says Jamie Burrows, cofounder and CEO of Vertical Future, who plans to expand into southeast Asia soon.

&ever is launching what it calls a ‘mega farm’ in Singapore towards the end of 2021, which will grow 1.5 tonnes of leafy greens per day, according to CEO Henner Schwarz. Liberty Produce was recently awarded funding to bring high-tech vertical farming projects to Singapore while iFarm is also gearing up to launch vertical farms in Asia between 2022 and 2024. Late last year, Infarm secured a deal with Japanese supermarket chain Sumitomo to sell its crops.

Eric Archambeau, cofounder and partner at VC Astanor Ventures, an investor in Infarm, thinks expanding into multiple markets is a good idea. “It can definitely make sense for companies to expand into new markets if they have a differentiated product mix that fits with the demands of the new market,” he says.

Who’s got the most cash?

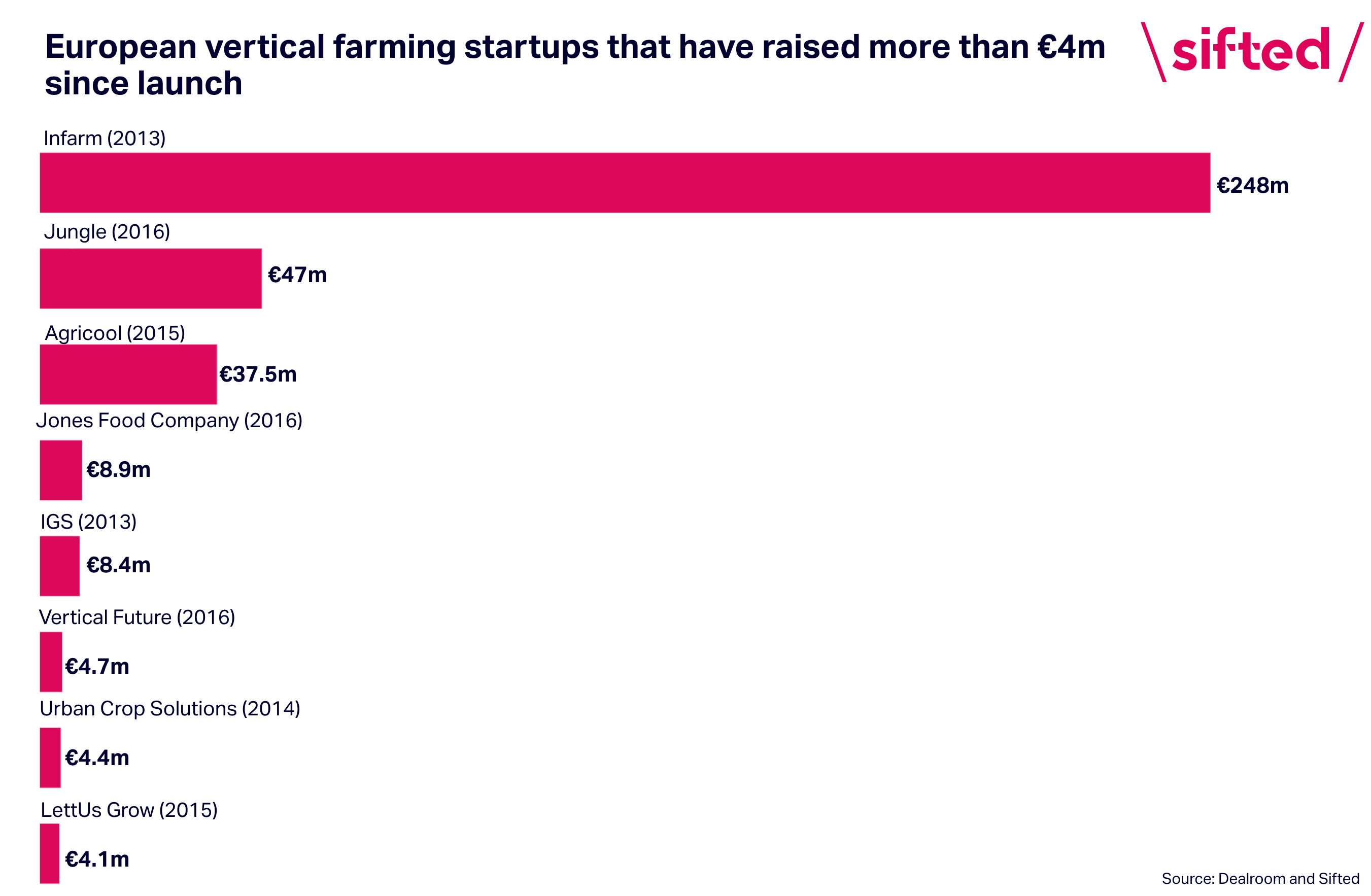

Infarm has raised by far the most money since launch :€300m+. It’s aiming to become profitable by 2023 and has hired Goldman Sachs to help it go public, reportedly via a SPAC. That could see it become Europe’s first vertical farming unicorn.

Next up is Jungle, which shot up to second place thanks to its recent €42m funding round. France’s Agricool follows slightly behind at €37.5m raised, but hasn’t publicly announced any funding since 2018.

Many of Europe’s prominent investors have backed one of the startups, including Atomico, Latitude and Daphni. Some corporate investors have also dabbled in vertical farming funding rounds, including Ocado and Bonnier. Non-European investors have also chipped in, including Agfunder and matrix partners, two San Francisco-based VCs.

On M&A, grocery tech giant Ocado now owns 70% of the UK-based vertical farm startup Jones Food Company.

Astanor’s Archambeau thinks that M&As will spice up in the future. “Smaller companies will likely be acquired either by larger vertical farm companies or by supermarkets,” he says.

“It is also likely that we will see sooner, rather than later, mergers between larger companies seeking to consolidate the market and expand their produce offerings and/or geographical coverage.”

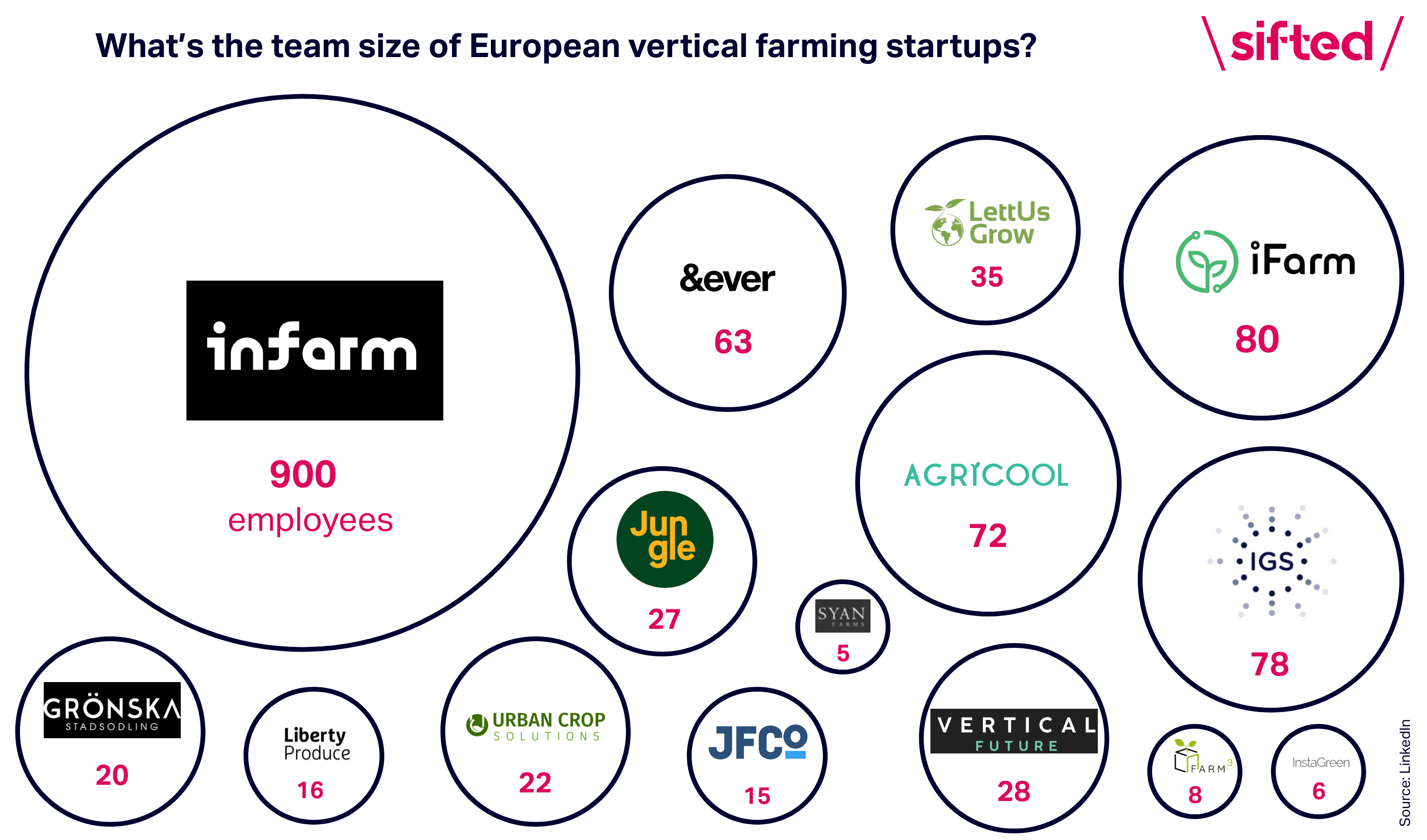

Unsurprisingly, Infarm has the highest headcount, followed by iFarm and Intelligent Growth Solutions. France’s Jungle says it wants to double its team of 27 by the end of 2022 and the UK’s Vertical Future plans to bring its headcount of 28 to 60 by the end of the year.

What’s next for the market?

While there’s appetite for the market to scale, there is still some room for improvement. Production cost is the big elephant in the room, says Archambeau.

“Having a viable financial model and an efficient farm is the main hurdle for vertical farming,” Gilles Dreyfus, cofounder of Jungle, told Sifted earlier this year.

But Jungle thinks it’s already cracked it by focusing on large-scale farms. It’s currently building a 5,500m2 farm near Paris, which it hopes will be operational by the end of the year. It plans to sell food for just 5% more than conventional alternatives, but 20% less than organic food grown on farms.

Infarm’s cofounder Guy Galonska told Sifted that scaling cheap renewable energy could also help lower costs. Solar energy could be an option: “If you look at the demand and supply curve of solar panels, they supply energy in the day, but energy demand is at night. That’s a place where vertical farming could go quite nicely.”